My understanding of the world – particularly the one we subconsciously create – evolved drastically when I read Plato’s Euthyphro. Socrates asks “Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?” establishing what has become commonly known as the “Euthyphro Dilemma”. More simply put – is something morally good because God says it is, or does God say its good because it is? The dichotomy is clearly predicated on religious undertones, but to me, is more valuable when taken beyond religion. I realize I am flirting with controversy, but please bear with me a moment.

I was born and raised in a theist family. Going into university, while I was by no means a staunch religious practitioner, I instinctively felt uncomfortable with the idea of atheism – either way, I did not pay much attention to my religious beliefs. I did, however, pride myself on a tendency to think logically and objectively about ideas. My love for deducing logical arguments and questioning unsound thinking grew further in Philosophy class – which is where I stumbled upon Euthyphro’s Dilemma.

It quickly became evident that from a theist lens, neither answer is particularly desirable. But despite my firm commitment to objective, open-minded thinking, I found myself unable to stomach the implicit troubles entangled with either conclusion. While there are undoubtedly compelling theist arguments in response to the dilemma, I personally was unsatisfied, and yet deeply hesitant to entertain atheist conclusions. It was my first conscious encounter with cognitive dissonance.

While the internal dialectic did not yield a confirmatory answer to the truth of the universe, I discovered something about the human condition: our default setting is to believe that we chose our beliefs, rather than actually choose our beliefs. To be clear – I do not know whether God exists, but it is unimportant – the insight was in acknowledging which reality I am programmed to root for.

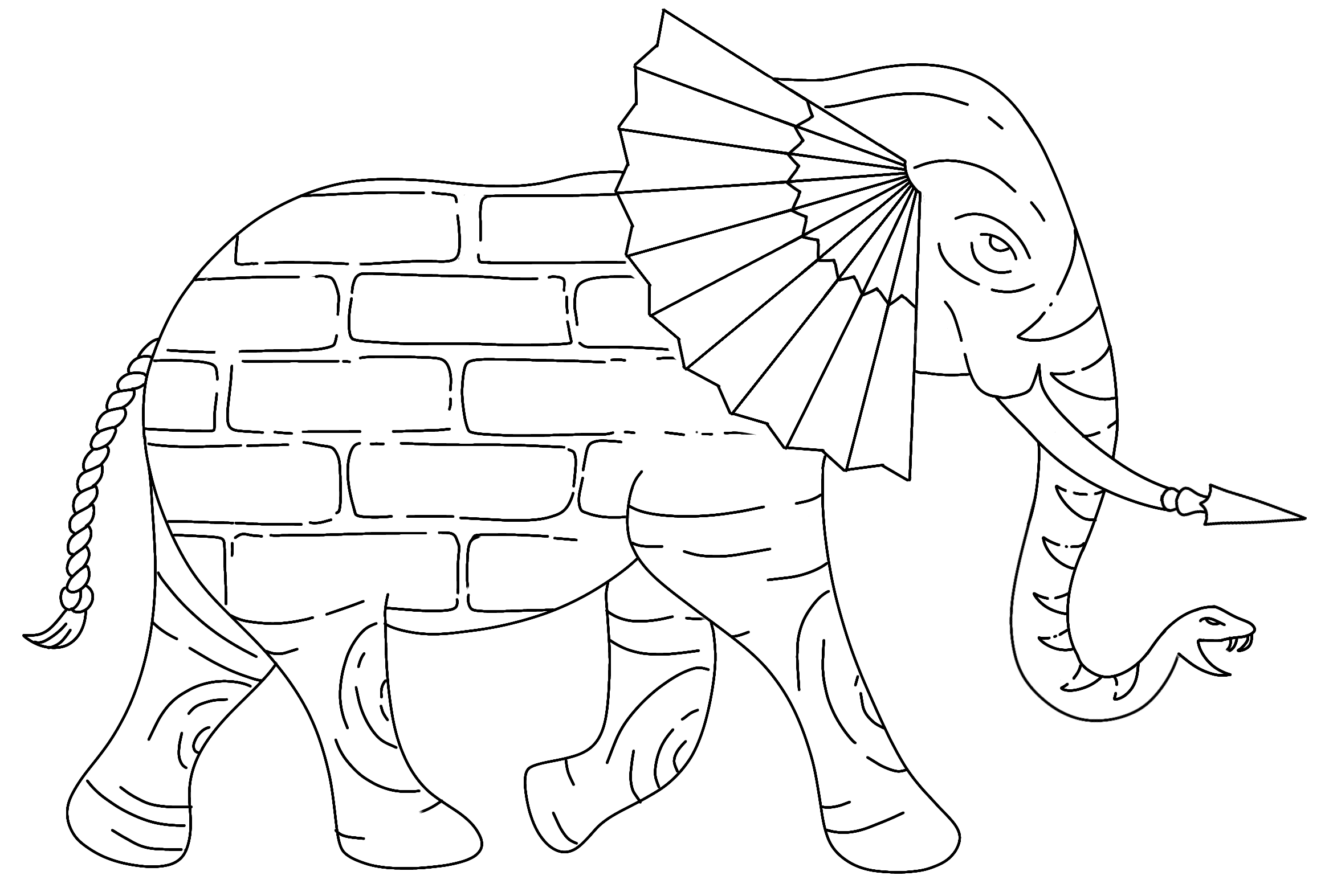

My revelation was followed by a deep suspicion – what other beliefs, values, and biases did I blissfully inherit? And more importantly, is it just me? The latter is something I have grown increasingly passionate about. If it is true that my predisposition is not atypical, then it seems to me that the walls that divide us – be they ideological, racial, or religious – have less to do with difference, and more to do with familiarity. The beliefs we vehemently wear as our identity – particularly to separate ourselves – may be nothing more than the prolific manifestation of parasitic ideologies. Of course, it would be naïve to suggest that we serve as vessels for a seemingly deterministic tale of humanity, but it does beg the question – if you woke up tomorrow with a reset mind, would you choose the same beliefs? I bet that as you read this, your answer is “yes”. Now imagine a world where the one trait we all share is the urge to delineate, coupled with an evolutionary duty to propagate.

In case you were wondering, I now consider myself a humanist theist. The irony is not lost on me – the oxymoron is a form of temporary compromise, because the dialectic lives on.